Will Symons on Bike Lanes as Everyday Transport

00:00 About Will

00:46 Will’s Thesis and Its Relevance

03:04 Challenges in Transport Planning

04:55 Navigating State and Local Government Barriers

08:33 Community Engagement in Transport Projects

10:40 Insights from Will’s Thesis

24:39 Future Directions and Final Thoughts

In this episode of People and Projects, I sat down in the studio with Will Symons, a transport planner whose work sits right at the intersection of policy, local government reality, and what actually gets built on the ground. The conversation grew out of a question that keeps resurfacing in transport planning: we know what needs to happen — so why isn’t it happening?

Will’s master’s thesis in urban planning tackled that question head-on, focusing on bike lanes and the institutional barriers that prevent them from being delivered as everyday transport infrastructure. What made this conversation particularly valuable is that Will is now working as a consultant, applying those research insights directly with local councils across Australia.

This episode is not about cycling as a lifestyle or bikes as a recreational activity. It’s about bike lanes as transport — how people move through cities, suburbs, and neighbourhoods, and why delivering safe, functional bike networks is still so difficult.

From Study to Practice

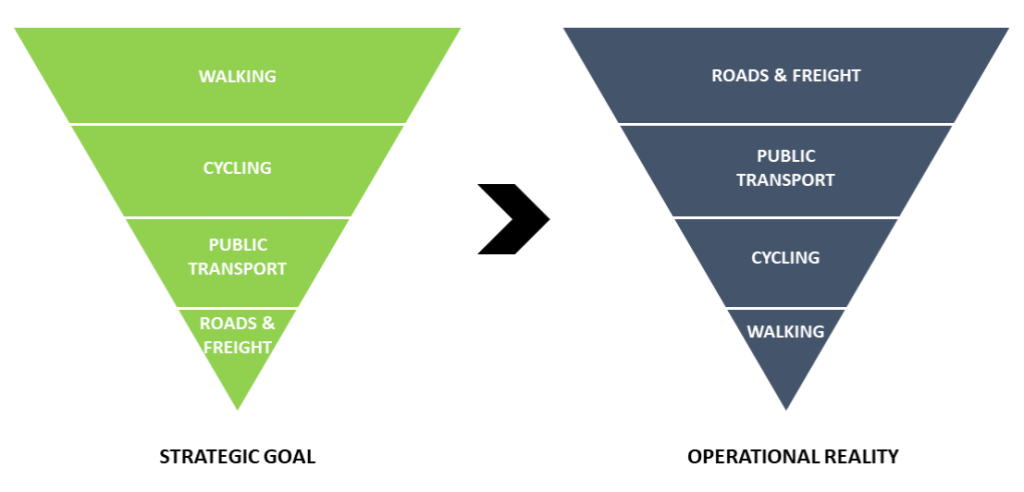

Will’s interest in transport planning emerged naturally during his studies. While completing his Master of Urban Planning, he found himself consistently drawn to transport-related projects, particularly those involving walking and bike infrastructure. Across different assignments and studios, one pattern kept appearing: governments at all levels talked positively about bikes, walking, and mode shift, but the physical infrastructure lagged far behind.

“There’s a clear trend where policies say the right things,” Will explained, “but there’s a gap between theory and practice.”

That gap — between strategic plans and what actually gets built — became the foundation of his thesis. His research focused on understanding the lived experience of transport planners working inside councils, and the barriers they face when trying to deliver bike lanes in Australian cities.

What a Master’s Thesis Really Looks Like

For listeners unfamiliar with academic research, Will’s thesis was a two-year research project completed alongside practical coursework. It involved interviews with council officers across inner, middle, and outer suburban Melbourne, analysis of planning frameworks, and a deep dive into how decisions around bike lanes are made — or avoided.

By the time Will completed the thesis, he had built a detailed picture of the institutional, political, and cultural forces shaping transport outcomes. That research has since become a practical lens he brings into his consulting work.

Understanding the Council Reality

One of the most valuable outcomes of Will’s research is a clearer understanding of what local government transport planners are actually dealing with day to day.

Councils often have small transport teams with limited resources, ambitious goals, and significant constraints. While they may want to improve bike access, they operate within approval systems that can severely limit what is possible.

In Victoria — and similarly in Queensland — councils require state government approval for changes near major traffic items such as traffic lights, roundabouts, bus stops, or state-controlled roads. Even small bike lane projects can trigger complex approval processes, delaying or derailing them entirely.

This creates a significant power imbalance between state and local government, one that planners must constantly navigate.

Designing Around the Approval System

Rather than fighting the system head-on, Will described how councils can work more strategically within it.

One approach is to prioritise routes that avoid state-controlled roads altogether. Disused land, drainage corridors, rail easements, or quiet residential streets can often form the backbone of a local bike network without triggering state approval processes.

Another strategy is aligning projects with state-endorsed plans such as the Principal Bicycle Network. When councils can point to state policy and say “this route already exists on your map,” it strengthens their case and improves the chances of approval.

These approaches may not deliver flagship bike lanes on arterial roads, but they can significantly improve everyday bike access at the local level.

The Untapped Potential of Local Streets

A major opportunity identified in Will’s work is the development of local bicycle networks. These focus on residential streets where councils have direct control and where small changes can have big impacts.

Simple interventions such as modal filters — which restrict through traffic for cars but allow bikes and pedestrians to pass — can transform neighbourhoods. Lower traffic volumes and reduced speeds make streets feel safer and more usable, even without major construction.

Councils are increasingly recognising that modest investments in local streets can dramatically improve how people move around without cars.

Community Engagement That Actually Works

One of the clearest lessons from Will’s research is that how councils engage communities matters just as much as what they build.

Traditional consultation often happens too late, presenting residents with near-final designs and asking for feedback on minor details. This approach tends to generate resistance rather than support.

Will described more effective engagement methods where communities are involved early — even before designs exist. In one project, residents were invited to ride proposed bike routes and share how they felt: where they felt safe, where they didn’t, and what needed to change.

This shifted the conversation from “do you support this design?” to “how should this street work for you?”

Outer Suburbs and Car Dependence

The challenges intensify in outer suburban areas. Will’s research included councils on Melbourne’s fringes, where rapid growth, limited public transport, and long travel distances create deep car dependence.

In these areas, car ownership often feels unavoidable. As a result, bike lanes are frequently perceived as competing with cars for space, rather than as transport infrastructure in their own right.

Council officers described strong community expectations around road widening, parking provision, and congestion relief — usually framed in terms of accommodating more cars. Bike lanes, by contrast, face higher burdens of proof.

The Burden of Proof Problem

A recurring theme in the interviews was that bike infrastructure is often required to justify itself far more rigorously than car infrastructure.

Residents and traders may fear loss of parking or changes to traffic flow, and these concerns can dominate public discourse. Will referenced the idea of a “hill of hysteria” — the intense resistance that often appears before change is implemented, followed by gradual acceptance once people see how it actually works.

Better communication, clearer explanations of benefits, and more transparent engagement can help councils navigate this phase.

Reframing the Conversation Around Safety

For individuals trying to advocate for better bike infrastructure — particularly parents, people with disabilities, or those with limited time and energy — Will suggested framing concerns in safety language.

Using terms like “near collision” or clearly documenting unsafe conditions can prompt more serious responses from decision-makers. Tools like the Healthy Streets Design Check can help residents articulate how a street feels and why it doesn’t function well for everyday travel.

These approaches provide structured, evidence-based input rather than informal complaints.

Councillors and Transport Teams

Councillors play a critical role in shaping transport outcomes, but they also face political risk. Will’s research found that councillors are often wary of backlash and negative perceptions, especially when change affects parking or traffic.

The most effective councillor-led projects tend to involve early engagement, curiosity about community needs, and close collaboration with council officers. Rather than announcing predetermined solutions, successful projects start with listening.

There is also significant latent demand for bike travel — many people would like to ride but don’t feel safe doing so. Making that hidden demand visible can change political calculations.

Signs of Institutional Change

One of the most encouraging parts of Will’s reflection came when revisiting his thesis recommendations. In the years since its completion, several institutional barriers he identified have begun to shift.

In Victoria, 30 km/h speed limits are now formally recognised and supported in policy, enabling councils to create calmer local street networks. Updated guidance on bike and micro-mobility infrastructure has also been released, providing clearer direction for practitioners.

These changes don’t solve everything, but they remove key obstacles that previously stalled progress.

Learning from Elsewhere

Will also shared insights from time spent studying transport approaches in the Netherlands. One small town, in particular, stood out for its people-centred mobility policy.

The policy is built around three core principles:

- Children have the right to travel independently

- Older people and people with disabilities have the right to move freely and safely

- Streets are shared public spaces, not just traffic corridors

By anchoring decisions in these values, transport planning becomes more accountable and inclusive. While Australian cities differ in context, these principles offer a powerful reframing of what transport systems are meant to achieve.

Moving Forward

This conversation with Will Symons highlights both the scale of the challenge and the real opportunities for change. Structural barriers are real, but they are not fixed. Policies evolve, guidelines update, and community expectations can shift.

Bike lanes, when treated as everyday transport infrastructure rather than optional extras, have the potential to reshape how people move through their neighbourhoods. The path forward is rarely fast or simple, but it is increasingly clear.

Thank you to Will Symons for sharing his research, experience, and optimism. And stay tuned for our upcoming conversation with Lucy Saunders, where we’ll continue exploring how streets can work better for everyone.

Article about Renkum Mobility Vision and Plan: https://urbancyclinginstitute.substack.com/p/renkums-bold-step-towards-people

About the hill of hysteria: https://thelabofthought.co/library/the-hill-of-hysteria and https://wbrassociation.org.uk/why-changing-our-environment-is-so-hard/

Will’s Masters thesis: https://minerva-access.unimelb.edu.au/items/9ee4887b-3d01-4149-aa88-112f2b6620f9

Austroads Cycling and Micromobility guidance: https://austroads.gov.au/publications/active-travel/ap-r724-25

Healthy Streets assessment tools: https://www.healthystreets.com/resources#on-street-assessment

Victorian State Government Department of Transport and Planning Speed Zoning Policy: https://content.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2025-10/Speed-Zoning-Policy-Edition-3-August-2025.pdf

The podcast episode with James Laing https://getaroundcaboolture.au/s2e2-pp-james-laing-making-cities-move-with-active-travel/

Podcast theme music: Doctor Yes | Yari | Bensound

GetAroundCaboolture.au